November/December 2024

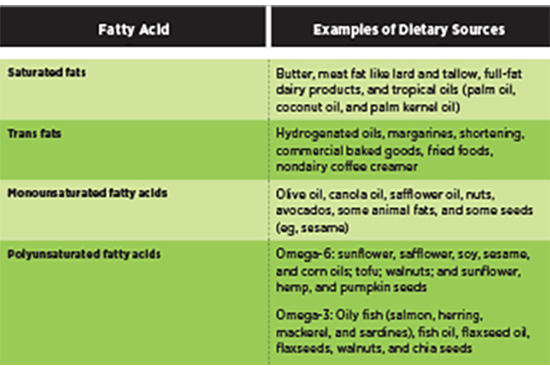

November/December 2024 Issue Eye Health: The Role of Diet in Preventing and Treating Diabetic Retinopathy At the most fundamental level, diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a metabolic disease of the retina. When excessive glucose is present in the bloodstream, as is the case with poorly controlled type 1, type 2, and gestational diabetes, several metabolic pathways are upregulated to handle the hyperglycemic state. One of these is the polyol pathway, which converts glucose into sorbitol and then into fructose. However, the polyol pathway’s capability is limited within the retina because this tissue does not have the enzyme required to complete the second half of the conversion. Thus, sorbitol builds to toxic levels, causing damage to the retina. Beyond the build-up of sorbitol, all of the upregulated pathways produce reactive oxygen species—free radicals that cause oxidative stress and inflammation within the delicate tissues of the eye.1 In addition to the metabolic changes within the retinal cells, the function of multiple cells that support the retina are also negatively affected by high levels of blood glucose. The blood-retinal barrier becomes damaged, the neurons that send signals from the eye to the brain lose functionality, and excess glucose and LDL cholesterol in the blood damage the tiny blood vessels that supply the retina, resulting in blocked blood vessels that can then leak fluid or blood.2-4 High blood pressure, whether caused by hyperhomocysteinemia, excess blood glucose, dehydration, or other root causes, also worsens eye damage by increasing the production of harmful free radicals and weakening the body’s natural defenses against them.4,5 Given the delicate nature of the retina and its supporting cells, it’s no surprise that DR is one of the most common microvascular complications of diabetes. In fact, it’s recognized as a leading cause of vision impairment and blindness among working-age adults globally.5 Specifically within the United States, an estimated 9.6 million people were affected in 2021, reflecting a prevalence rate of 26.43% among people with diabetes.6 Among these patients, a larger percentage are 65 years of age and older, as prevalence for diabetes and DR increases through young and middle adulthood and peaks in older adulthood.7,8 The CDC estimates that 29.2% of individuals aged 65 and older have either type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), making the need for intervention and prevention crucial for this population.8 The Link Between Diet and Diabetic Retinopathy Specific eating patterns and appropriate supplementation can combat oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which are critical in DR pathogenesis. Glycemic control, lipid profile management, and blood pressure regulation are integral to reduce the risk of DR, and all can be positively influenced through appropriate nutrition interventions.4 Nutrient-Dense Diets Since fiber plays a crucial role in glycemic control by slowing digestion and therefore slowing the absorption of glucose, adequate fiber intake is crucial for the effective management of diabetes and reducing the risk of developing retinopathy. Specifically, several studies have found a protective effect from DR with increased dietary fiber intake.9 Dietary eating patterns that promote nutrient-dense and fiber-rich foods can help ensure individuals consume all of the healthy fats, fiber, vitamins, and minerals necessary to prevent or slow the progression of retinopathy. The Mediterranean diet is an example of an eating pattern that achieves these dietary goals, and multiple studies have shown a significant protective effect against DR when it is followed.4,9 For example, the Mediterranean diet enhanced with olive oil or nuts was associated with a respective 44% and 37% reduced risk of retinopathy in a six-year prospective study that included 3,600 participants.4 In their study of 1,200 people with type 2 diabetes, El Bilbeisi et al found that people who followed an “Asian-like” eating pattern, characterized by high intake of vegetables, fruit, legumes, and whole grains, had lower odds of developing diabetic complications when compared with those who followed the “sweet-soft drinks-snacks” dietary pattern.10 Of course, within these healthful eating patterns, caloric intake should be maintained within the range needed for the individual’s age, activity level, medical conditions, and personal goals. Some studies have shown an increased risk of DR progression with a high total calorie intake.9 As well, although supplementation should be considered in certain circumstances, the primary goal is to consume whole foods due to their fiber content and comprehensive nutrient profiles. Role of Fatty Acids In particular, one study found consuming oily fish, like salmon, mackerel, and sardines at least twice per week can reduce the risk of retinopathy by up to 70%.4 Another study found that consuming 500 mg per day of omega-3 fatty acids considerably lowered an individual’s odds of developing DR.5 That being said, a third study showed no significant association between fish oil supplements and DR risk, indicating the importance of whole food sources.9 As well, oleic acid, a specific type of monounsaturated fatty acid, may have a protective effect against DR.9 Oleic acid can be found naturally in many foods including olive oil, sunflower oil, chicken, pork, cheese, cashews, and avocados. The following table highlights some of the primary sources for diabetes-promoting and diabetes-preventing fatty acids. Micronutrients and Antioxidants Antioxidants are critical in stabilizing cell membranes and preventing oxidative damage, a key contributor to DR progression.4 Retinoids such as lutein and zeaxanthin, which are abundant in dark leafy greens and egg yolks, are particularly beneficial in maintaining retinal health and have been shown to both decrease the risk of DR and delay its progression within five years.4,5 A crucial component of the antioxidant enzyme Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase, zinc is present in high concentrations in the retina, and decreased serum levels in diabetic patients with retinopathy may be a contributing factor to increased oxidative stress and the progression of DR.11 Other antioxidants include coenzyme Q10, copper, manganese, selenium, and alpha lipoic acid, a powerful antioxidant within the retina’s ganglion cells and pigment epithelial cells.5 Polyphenols, such as those found in coffee and green and black tea, offer further antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits.5,9 In multiple studies, tea consumption has been shown to have a protective effect against DR.9 Green tea has been shown to protect retinal neurons and regulate the subretinal environment by reducing reactive oxygen species, while black tea can lower blood sugar levels. Polyphenols that have shown a positive impact on glycemic control and free radical activity include resveratrol, chlorogenic acid, and lycopene.4 Although the goal remains to consume all of the needed micro- and phytonutrients from whole foods, supplementation may be needed. For example, polymorphisms in the MTHFR gene can reduce the generated enzyme’s ability to methylate folate, resulting in hyperhomocysteinemia.5 For individuals with these polymorphisms, the use of a supplement with L-methylfolate can help prevent the buildup of homocysteine and the subsequent hypertension and epithelial damage that can occur. Conclusion — Stephanie Dunne, MS, RDN, IFNCP, is an integrative registered dietitian, freelance writer, and owner of Nutrition Q.E.D., in St Petersburg, Florida.

References 2. Antonetti DA, Silva PS, Stitt AW. Current understanding of the molecular and cellular pathology of diabetic retinopathy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(4):195-206. 3. Diabetic retinopathy. National Eye Institute website. https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/diabetic-retinopathy. Updated August 2, 2024. Accessed August 6, 2024. 4. Bryl A, Mrugacz M, Falkowski M, Zorena K. The effect of diet and lifestyle on the course of diabetic retinopathy—a review of the literature. Nutrients. 2022;14(6):1252. 5. Rondanelli M, Gasparri C, Riva A, et al. Diet and ideal food pyramid to prevent or support the treatment of diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, and cataracts. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1168560. 6. Lundeen EA, Burke-Conte Z, Rein DB, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the US in 2021. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023;141(8):747-754. 7. Magliano DJ, Boyko EJ; IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th Edition Scientific Committee. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 10th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2021. 8. Diabetes data and research. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html. Updated May 15, 2024. Accessed July 30, 2024. 9. Shah J, Cheong ZY, Tan B, Wong D, Liu X, Chua J. Dietary intake and diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review of the literature. Nutr. 2022;14(23):5021. 10. El Bilbeisi AH, Hosseini S, Djafarian K. Association of dietary patterns with diabetes complications among type 2 diabetes patients in Gaza Strip, Palestine: a cross sectional study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2017;36(1):37. 11. Dascalu AM, Anghelache A, Stana D, et al. Serum levels of copper and zinc in diabetic retinopathy: potential new therapeutic targets (review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23(5):324.

|